The announcement of the release of Call of Duty: Black Ops 4 on 12 October 2018 was greeted with international fanfare. The previous release from the Call of Duty franchise brought in $500 million of revenue within three days of its release and went on to generate over $1 billion by the end of the year.

The latest on the rumour mill is that Black Ops 4 will include a “battle royale” mode, a game in which a large number of players are challenged to survive, search for weapons and eliminate opponents while staying within the confines of a shrinking “safe zone” – last player or team standing wins. This game genre, named after the 2000 Japanese film Battle Royale, shot into the spotlight in 2017 with PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), which sold over 25 million copies in 2017; Fornite surpassed this in 2018, becoming a cultural phenomenon.

Somewhat predictably, this has led some to call out against what they see as companies rushing to profit from the battle royale trend started by PUBG. In fact, PUBG’s creator Brendan Greene has been claiming that PUBG needs stronger protection against copycats and that existing IP protection is inadequate.

Protection available

A patchwork of registered and unregistered IP rights protect many aspects of games in Europe. For example, design rights can be used to protect unusual user interfaces, copyright and trade secrets legislation can protect source code from being copied by unscrupulous developers, and trade marks can protect a game’s distinctive logos, shapes, sounds, and even movements.

In addition to protecting the software, copyright can protect the graphical elements of a game, from the appearance of the characters, the menus and maps to the soundtrack or sounds used, assuming they meet the originality requirements.

Although there is no copyright in the general idea of battle royale games, original ways of expressing such an idea are protectable. A helpful analogy is that although there is no copyright protecting the idea of fantasy novels populated with elves and dwarfs (which has been done countless times before), writing a story about two likeable hobbits called Frodo and Samwise getting past troublesome orcs, with help from elves and a powerful wizard, to dispose of a ring of power in the belly of a volcano is likely to land you in some trouble.

The more “densely populated” a particular field is, the narrower such copyright protection is likely to be. Considering that PUBG is not the first battle royale game – Minecraft Hunger Games (2012); Arma2 DayZ Battle Royale (2013); Ark: Survival of the Fittest (2015); H1Z1 (2016); and The Culling (2016), amongst others, preceded it – copyright protection in elements which comprise its expression of the battle royale genre is likely to be narrow.

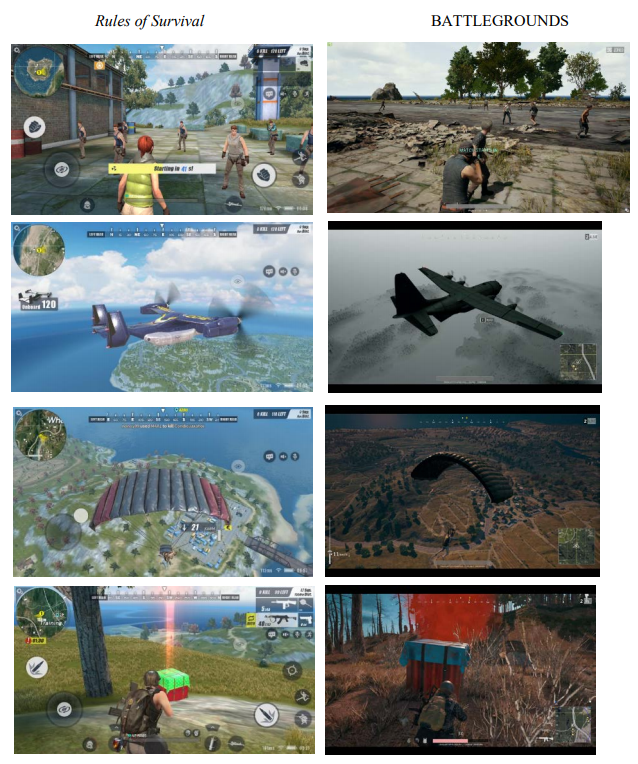

However, the patchwork of rights available should provide sufficient ammunition to remove clones and direct copycats from the market. Indeed, in April PUBG filed a 154-page complaint in California which alleges copyright infringement, trade dress infringement (a similar cause of action to passing off under UK law), and unfair competition against two other games: Knives Out (KO) and Rules of Survival (ROS). The complaint is not merely that these other games are based on the battle royale concept but that there is substantial copying of many of the individual elements of PUBG, as illustrated in an extract of the complaint below. If PUBG are successful, they could benefit substantially were an award of damages to be made; global monthly revenue for KO in was estimated at around $24 million for February 2018.

Extract from paragraph 56 of PUBG Corp. and PUBG Santa Monica, Inc. vs NetEase, Inc. and NetEase Information Technology Corp filing in US District Court, Northern District of California.

Interestingly, PUBG has also just filed a complaint against Epic Games, the developers of Fortnite, in South Korea. Early reports suggest that PUBG again alleges copyright infringement as regards the user interface and in-game items. The two companies have a contractual relationship which may further complicate matters and could potentially give rise to contractual claims or form the basis for an allegation that game materials had been shared between the two companies and this resulted in copying.

Are patents relevant?

Patents provide a patentee with an absolute monopoly for 20 years in exchange for their disclosure of a novel invention (“the patent bargain”). Unlike in the US, in the UK computer programs are excluded from patent protection, unless they either make a “technical contribution” to what is already known in that field. So a new set of rules in a game will generally not be patentable as it lacks technical effect, but a new probability calculation to make encounters with other characters more unpredictable to the player would have a technical character. But patent protection can take years to obtain and is relatively expensive, so is not always appropriate in a fast moving field such as computer games.

Do IP laws need amending in the age of gaming?

The fact that game genres, such as battle royale, are not protectable in and of themselves is no bad thing. It would not be in the interests of consumers to give any one entity a monopoly in any game genre for any period of time – that entity could end up doing a poor job or abandoning the genre entirely, for whatever reason, leaving consumers’ demands unfulfilled and stifling competition and innovation. As Brendan Greene said:

“I want this genre of games to grow. For that to happen you need new and interesting spins in the game mode. If it’s just copycats down the line, then the genre doesn’t grow and people get bored.”

IP rights need to strike a delicate balance between protecting against copying while encouraging innovation. And innovation can itself be inspired from previous works, as long as inspiration does not step over the line into infringement.